Back when I was a youth, and I read the comic books in chapbook form, one of my regular monthly buys was Grendel. Written and occasionally drawn by Matt Wagner, and initially appearing as a back-up feature in Comico publications, by 1986 Grendel was its own monthly title, and ran as such to 1990. After 40 issues, Comico was bankrupt, and Wagner moved to Dark Horse where Grendel persisted in a succession of mini-series. Grendel Tales, another series featuring work by Wagner but showcasing other writers taking on the Grendelverse, appeared in the ‘90s, as did two DC miniseries written and illustrated by Wagner pairing versions of Grendel with Batman.

Its publication history- spanning formats, publishers, and collaborators- is already complicated, especially for a creator-owned title. But the design of the series itself is also unusually complex. Grendel’s is not an alter-ego in the same sense as other comic characters; Grendel is, to its core, about a persona that travels through or is adopted by a range of highly disparate characters in divergent storylines, settings, and periods. This played out satisfactorily across the various incarnations of Grendel and Grendel, but the narrative complexity, the profusion of characters and events linked less by causality than by thematic continuity and divergence, yet with intricate cross-references between them, meant that it was difficult for me, at least, to fully appreciate in pamphlet form what Wagner had accomplished with the series as a whole. There had been graphic-novel collections of Grendel stories, but even these were spotty and incomplete. Some issues were never reprinted at all.

Because of all these factors- publishers, monthly and mini-series, different characters, different timelines and settings, Wagner and others returning to earlier story phases to fill in gaps- Grendel has had an unusually, maybe a uniquely complicated history. I want to argue that while Wagner’s work made Grendel an exemplary title in the ‘80s and ‘90s, its jumpy, spotty publication history and the relation of individual chapters in the Grendel mythos to the whole prevented it from achieving the status it deserves. The Grendel Archive edition published in 2007 seemed to indicate that Dark Horse was finally going to bring some order to all this, but only one collection ever appeared. Moreover, Behold the Devil, a miniseries focusing on a “previously unknown” episode in the career of the first Grendel, appeared in 2010, rendering even that anthology obsolete.

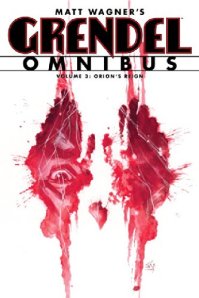

But in the last few years, a new comics re-publication format has emerged, the omnibus: smaller in height and width than the original issues, but printed on quality stock, relatively inexpensive, and very thick. The size of the omnibus can be an issue (making art smaller never helps appreciation, but add in downsizing dialogue and exposition, they can be actively annoying to read), but for reprinting older and less in-demand material in the middle of a recession, it is a format whose time has come. Whatever its limitations, it is the perfect, the ideal format for Grendel, and from 2012 to 2013, Dark Horse published four volumes in the Grendel Omnibus series (four Grendel Omnibuses? Grendel Omnibi?) The omnibus edition, finally, has resulted in an ordered, story-chronological publication of the entirety of the Grendel stories to date. Putting it into this format finally reveals Grendel for what it is, but which has never been so apparent before, at least to me: one of the great comic book masterpieces of its time. Archive editions tend to republish stories in order of publication; the Grendel omnibus series not only reorganizes texts into story-chronological order, but does so in such a way as to highlight the intellectual and artistic threads of the entire set, rendering the whole coherent to an unprecedented degree.

Wagner had begun publishing work about the first Grendel, one Hunter Rose, in 1982 in the Comico Primer series. When he reintroduced Rose as a back-up feature in his Mage series, in a story then collected as Devil by the Deed, he extensively revised this first telling of the tale. At the conclusion of Devil by the Deed, Grendel/Rose is dead. The history of comics has innumerable instances where a character is killed and another character takes up their mantle, but this is usually temporary. The Batman, Superman, Captain America, Spider-Man titles… all have featured replacements for Bruce Wayne, Clark Kent, Steve Rogers, and Peter Parker at one time or another, but brought them back after a few months. The Flash and the Green Lantern have experienced more permanent changes. Thus far, in the DCU the identity of the Flash has been Jay Garrick (1940-), Barry Allen (1956-1985 and 2008-), Wally West (1986-2006 and 2007-2012), and Bart Allen (2006-2007). Except for poor Bart, though, each other Flash has taken the role for decades at a time. The Green Lantern has variously been Alan Scott, Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner, and Kyle Rayner, along with John Stewart and Simon Baz.

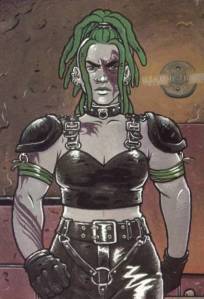

Okay. But Grendel is different. Changes in the identity of Grendel happened every 10 issues or so (sometimes much less), each incarnation usually ending in Grendel’s death. With a few exceptions (eg., from Christine Spar to Brian Li Sung), each Grendel has appeared in an entirely distinct historical period, the series moving from near- to far-future in the course of its run. No two Grendels were mistaken for each other; where a random villain might not be aware than Wally West had replaced Barry Allen, each Grendel had a distinct identity and persona. Only one thing unites them all, and it is more thematic than causal: the use of violence as a tool. None of these Grendels is a hero. Some are anti-heroes, some victims, some utterly villainous. Hunter Rose, in particular, is fully a supervillain; Christine Spar closer to a heroine, but one whose actions have become quite dark by the end of her story; and Brian Li Sung simply a victim. Eppy Thatcher was a deranged drug addict; Orion Assante, eventually, a world ruler; and the last, Grendel-Prime, a nameless cyborg.

As the first Grendel, Hunter Rose became something of a mythical figure, and touchstone, in the world of the stories. For readers, Rose’s tragic ending cannot overcome the impression made by his stylishness and his ferocious, almost superhuman intelligence and competence. Even though Devil by the Deed was dwarfed in length by later tales, for these reasons the appeal of Rose as a character has taken on a life of his own to one side of continuity. Thus, over the years, Rose has been the character Wagner has most often revisited, filling in gaps, elaborating on details and phases of Rose’s life treated summarily in Devil by the Deed, and pairing him off against DC’s Dark Knight.

The first volume of the omnibus collects all of the Rose stories to date, despite the fact that many of these stories first appeared years or decades after Devil by the Deed. The omnibus is, then, roughly chronological according to the Grendelverse, but not the publication history. In that sense, volume 1 is chronological, starting with the first Grendel stories, but also topical in that it groups stories around character biography. Unified in the first instance by Rose’s presence at their center, these stories are also unified aesthetically. Initially, Rose stories were presented with only three colors, black, white and red, though the first graphic album publication of Devil by the Deed was full-color. In volume 1, Devil by the Deed reverts to black, white and red, and is followed by two separate series of individual, single-issue Grendel tales centered on Rose and maintaining the color scheme, Black, White, & Red, and Red, White, & Black. Filling out the volume, and still with that color scheme, are “Sympathy for the Devil” and Behold the Devil.

Devil by the Deed lays out the framework of Rose’s life and adventures in some 38 pages of highly stylized illustrations, showing from the beginning a keen interest on Wagner’s part in page design, and accompanied by chunks of text “excerpted from” a supposed prose biography of Rose by Spar, the daughter of his ward, Stacey Palumbo. It tells Rose’s life story in brief, concentrating on his career as a novelist and super-criminal, and eventually settling on a kind of quasi-familial triangle between Rose; Palumbo, who he adopts after, as Grendel, killing her father; and Argent, an enigmatic werewolf just as beloved of Palumbo as Rose himself, and whose life mission is to destroy Grendel. When Stacey discovers Rose is Grendel, she shows a Grendel-esque skill at manipulation as she pulls strings to arrange a final confrontation between Grendel and Argent. Told in such a concise, telegrammatic form, Devil by the Deed leaves as many questions as answers, and so Black, White, & Red and Red, White, & Black go back and forth over aspects of Rose’s life to fill out the narrative. The first issue of the former, “Devil’s Advocate,” shows a lawyer chosen by Grendel to handle his legal business, such that his life becomes tied to Grendel on penalty of death. This serves to fill out the picture of how Grendel operates as a crime boss, which Wagner returns to throughout these two series. The next three, “Devil on My Back,” “Devil’s Apogee,” and “Devil’s Requiem,” turn back the pages on Rose himself, taking us deeper into his childhood and adolescence to show us how this boy became capable of fashioning himself into such a fearsome creature, how violence, rage against humanity, and a sense of superiority made him into Grendel. Devil by the Deed tells us that an affair with an older woman who believed in Rose’s exceptionalism helped turn him into Grendel, but these stories show it happen, and give it emotional depth.

From there, Wagner looks at various characters, from Rose’s editor to hitmen to small-time thugs to rival gang-members to witnesses and other human loose-ends, to elaborate our sense of how Grendel works, how he instills fear and controls people, how his activities become a kind of web ensnaring everyone in his sphere of influence. These become stories about power: how Grendel uses it, principally using fear and the threat of death to shape the world around him to his own benefit. One such story, “Devil’s Mate,” juxtaposes Rose teaching Palumbo chess with Grendel conducting his business, highlighting the cold logic of his actions. “Devil’s Garden” extends this, a similar juxtaposition allowing Rose to teach Palumbo about predators, and Wagner to draw an analogy between Rose and a spider in his garden. Other stories, like “Devil’s Labyrinth,” centering on Argent, flesh out the psychology of characters only cursorily described in Devil by the Deed (hereafter DBTD). A number of them highlight Larry Stohler, something of a mystery in the first tale. Early in DBTD, Stohler figures out that Rose is Grendel, but uses this information to insinuate himself into Grendel’s operations, becoming his right-hand man, and the only person Rose trusts. Stohler remains a key figure in the rest of the story, but his motivations and interior life are left unexamined. Gradually, across the singleton b/w/red tales, we understand more and more about who Stohler is and why he does what he does (at significant personal risk; knowing who Grendel is is dangerous information). Other stories center on Palumbo and her growing understanding of her caretaker. Red, White, & Black, though again made up of seemingly stand-alone noirish tales, has a slightly stronger thread through it, in that several of the tales center specifically on Grendel consolidating his power at the expense of rival gangsters, and ends with a series of stories showing the circumstances around the final Grendel/Argent battle from varying perspectives.

The black/white/red stories are like the shards in a stained-glass panel, each one adding some small piece to forming a full reflection of Rose, his life, and his times. Each one is stylistically distinct; they all have the same color scheme, but each issue is by a different artist, often in a radically different style.

Some stories are standard comic-book narration; others are framed as flashbacks, or constructed around thematic parallels and analogies; others are narrated in the style of DBTD, as chunks of texts accompanying illustrations. One, “Devil’s Toll,” consists of illustrations with each panel accompanied by a single word commenting on each phase of the action; another, “Devil’s Karma,” consists of full-page illustrations accompanied by haiku. I first read these stories as separate anthology-style series, and the stories work well on this level. But put together as appendices to DBTD, they gain immeasurable power: going back and forth over Rose’s life, oftentimes covering the same narrative ground but from multiple perspectives, highlighting the labyrinthine, chess-like quality of Grendel’s machinations. Taken together, then, the Rose stories, as they comprise volume 1 of the omnibus, become a tour-de-force of narrative complexity and formal innovation, far more impressive taken as a whole in this form than as individual issues. Behold the Devil, concluding volume 1, integrates the stylistic approaches seen in DBTD and the black/white/red stories to an extraordinary degree: within this single tale, we get the same multiple perspectives and even some of the stylistic variations as in the two series of b/w/r stories. Most daringly, via occult means, Rose foresees not his own future but that of Grendel itself: glimpses of Christine Spar, Eppy Thatcher, Grendel Prime. Here, just as we leave the first omnibus, Wagner lays out a kind of thesis about Grendel as a transpersonal force, as a personification of violence and will through ages and circumstances. Placed at the end of volume 1, it’s a transition, a preview, and a statement of intent. It could only work as such placed at the end of volume 1, as the capper of the epic of crime and revenge that volume 1 specifically is.

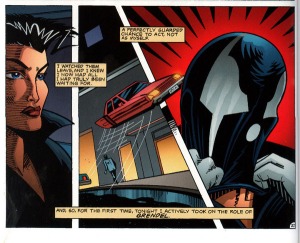

Volume 2, then, shows the Grendelverse expanding on several fronts. Here, the stories are long-form, and in full color. Most centrally, here Grendel first shifts from a single person into a kind of idea, a persona taken as a channel for the rage of those who adopt it. Devil Child, the opener, might actually be the darkest chapter of the saga. Written by Diana Schutz, Wagner’s Comico editor, it shows the truly horrific life suffered by an institutionalized Stacey Palumbo after Rose’s death. As powerful as this 1999 miniseries might have been in itself, it becomes much more satisfying in the continuity as a prelude to Devil’s Legacy from 1986, by clearly explaining how Grendel might be more real to Christine Spar than the mother who she barely knew.

Devil’s Legacy finds Spar a successful journalist and single mother living in New York and enjoying the huge success of her Hunter Rose biography, Devil by the Deed. But when her son is kidnapped and eaten by a troupe of Japanese kabuki vampires, there is little legal recourse available to her; the troupe, and it’s leader, Tujiro, have been doing this for centuries, and cover their tracks perfectly. Having written about Grendel, having spent so much time absorbed in him, she becomes him to take revenge.

She is pursued by a now-disabled Argent, and NYPD Capt. Wiggins, Argent’s slick aide and advisor. Finally, though, being Grendel destroys Spar, leaving behind her lover, Brian Li-Sung, who by the end of Devil’s Legacy has witnessed enough of the truth behind Spar’s actions that he himself is scarred by it. Spar had met Li-Sung when traveling to San Francisco in pursuit of Tujiro; after her death, to feel closer to her memory, Li-Sung travels to New York. There, his sense of loss and his alienation turn darker and darker, until finally he decides to adopt the Grendel mask as a way of achieving catharsis. This turns from random acts of violence to a concerted attempt to punish Wiggins for his role in Spar’s downfall. But of all the Grendels, Li-Sung is the least capable (finally, he is just a stage manager), and his tale comes to a quick and pathetic end.

The appeal of volume 1 is largely cerebral: first, one may appreciate the formal and stylistic audacity of the varied approaches to Grendel storytelling, and the intricate interrelationship of all the separate parts of Devil by the Deed, Black, White, & Red, and Red, White & Black. Second, Rose’s story encourages us to think about violence, fear, ego, will, and power in themselves, as ideas, the application to the characters’ lives being examples to flesh out and nuance them. Third, Rose is fascinating but not really relatable. In that sense, we are encouraged to think about the appeal of the villain. But that appeal soon proves relevant on other levels, because volume 2 is really the one that elicits the strongest emotional response. The appeal of violence and even villainy comes through in Spar and Li-Sung’s lives as responses to the terrible things life can do to people. If you emotionally invest in her, there are few things in comics quite as horrifying as Spar looking at her son’s eyeball having been pulled out of its socket. Li-Sung is pathetic, but one can at least identify with his alienation in the big city. In both cases, there is an intellectual dimension, but rooted in emotion: the reader is thinking, but about the appeal of extreme responses to those things we have or feel no control over.

At the end of volume 2, we go to the issues following Li-Sung’s death, featuring Wiggins, now an old, pot-bellied man, retired on his pension to a tropical beach. To earn some money, Wiggins goes all the way back to Rose, in fact following the Spar character’s lead by writing stories of that first, still most famous Grendel. This is the first really awkward bit of the omnibus editions: haven’t we already done Rose? If these are Rose stories, why not put them in volume 1? Given the Devil Tales issues were published much earlier than the black/white/red series, they feel rather like a dry-run for them; Wiggins follows the format Wagner would pursue in those of telling stories that fill out Rose’s adventures by focusing on somewhat tangential characters who are, for Rose, loose-ends in his criminal enterprises, and therefore doomed. But given that these stories are framed by Wiggins’ telling, and Wiggins first appears in Devil’s Legacy, they end up here. This is not, then, the best proof of my argument: that the omnibus edition is contributory to a sense of Wagner’s accomplishment rather than just a format that is a more or less a neutral factor in appreciation of the series.

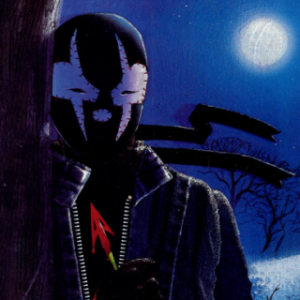

But the kicker comes in the opening section of volume 3, The Incubation Years, a series of never-before-reprinted stories bridging the continuous chronology of volume 2 and the jump into the far, and much less recognizable, future of God and the Devil. The first tells the story of how Wiggins, now a rich writer with a trophy wife on the back of the success of his Grendel books, is gradually taken over by hatred and paranoia, and driven to murder. Grendel becomes no more or less than a concept here, as if reclaiming his/her’s/it’s due from Wiggins for the latter’s success; it becomes a story of an unwitting bargain with the Devil. The succeeding stories, likewise, show Grendel as a force that one lets into one’s life at one’s peril, because in the end Grendel will take over. Each story focuses on a single individual who, in ways varying between literal and metaphorical, loses him or herself to Grendel and Grendel-ness; the backdrop takes us up to and through an apocalypse, the post-apocalypse migration to the western United States, and the growth of a theocracy in what’s left of North America.

This sets the stage for God and the Devil, another sustained series centering on Orion Assante, an aristrocrat, social progressive, and atheist who valiantly fights the power of a deeply evil papacy, and specifically a pope who first appeared as an appalling villain in Devil’s Legacy. The entire rest of the Grendel run is set up by God and the Devil: its characters, its conflicts, its world. In it, Grendel is incarnated in a profoundly alienated, drug-addicted, addle-pated, poor, child-abuse sufferer called Eppy Thatcher. It is the most straightforward storyline in Grendel in that it has clear-cut villains, the Pope and Pellon Cross, the head of police and the Pope’s minion; a clear-cut hero, Orion Assante; and an sympathetic-in-spite-of-himself anti-hero, Thatcher.

But God and the Devil is transitional not only in the literal sense of sketching out the world that the rest of the series will inhabit, but also in setting up Devil’s Reign, the crux of the Assante storyline. Indeed, that story lends its title conceit to that of the volume 3 as a whole, Orion’s Reign. While Devil’s Reign is punctuated by back-up stories showing the survival of an extended family of vampires led by Pellon Cross (infected in God and the Devil), it concentrates on Assante. With the best of motivations but increasingly cunning means, across Devil’s Reign Assante becomes the ruler of a chaotic world on which he wants to instill order and an imperial peace; in order to further these goals, he aligns himself with the Grendel mythology, finally dubbing himself the Grendel-Khan. The critique of organized religion is furthered here as Orion develops from a staunch, principled atheist to a kind of god himself.

This returns us to the kind of moral quandary that drove Devil’s Legacy, whereby a person with good intentions adopts and is in some sense taken over by Grendel, as a persona and as a concept, such that Wagner can examine violence exercised as a force of will, as a means to assert power. This is not mere repetition, but a radical widening of scope: if Spar was an anti-hero driven to violence, and finally “evil” for valid, relatable reasons, Assante likewise has positive intentions, but uses violence as a tool to become, ultimately, a fascistic potentate. This is the will-to-power on a global scale, where Assante’s noble ideals curdle into something much more sinister by the very nature of realpolitik. Assante himself never becomes a villain as such, yet finally all that he has wrought is thrown into question by means which have led inevitably to the end that is a world where the Grendel-Khan and his international police force of “Grendels” rule with a velvet glove cast in iron. Only towards the end of Devil’s Reign do we achieve enough emotional and narrative distance from Assante and his struggles to view them as an allegory of creeping moral compromise and political imperialism, which has a profoundly disquieting effect given we have been on Assante’s side for so long by this point. Even here, he remains somewhat sympathetic by virtue of the fact that his opponents are yet more corrupt while his intentions are never exactly malign. This is an exploration of the morality of Grendel in an entirely new context, on a world stage, literally and thematically: violence and power not just as a personal temptation, but as an outgrowth of systems and institutions and political trade-craft. Reading about Hunter Rose, the reader might be implicated via the appeal of villainy; reading about Christine Spar, the reader might be implicated via our sympathy for her; reading about Orion Assante, we are implicated first by our sympathy for him, but then too via our tacit participation in Western political hegemony, and specifically (for those of us from the States), American global dominance. By this point, Wagner has completed a leap from microcosm to macrocosm in his exploration of forms of evil and the moral questions to which they give rise.

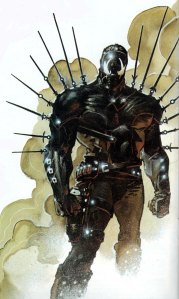

Volume 4, Prime, pursues the implications of the Grendel-Khanate, and concludes the tale (to date). War Child, the first series here, is another straightforward adventure tale, at least for most of its run. In it, Assante has died and his faithless, manipulative, power-hungry wife Laurel has become Regent. Her power is rooted in keeping Assante’s son Jupiter in captivity. Jupiter is “kidnapped” by a cyborg in Grendel costume, Grendel Prime, who in fact was tasked by Orion to protect the child and help Jupiter taking the reins of power.

Jupiter, Grendel Prime, and their compatriots are heroes here. Only at the end, when Laurel (her life already in ruins) is gruesomely punished for her “transgressions,” is a reader likely to begin to feel a bit queasy about the whole thing. The final story in the volume, Devil Quest, doesn’t particularly add much to Wagner’s project, and while it again shows the destructiveness of Grendel for anyone who gets too close to its power, narratively it doesn’t lead to much except to fill in the background to the second Grendel/Batman series. Of more significance is Past Prime, placed in between War Child and Devil Quest, taking the form of a prose novella written by Greg Rucka with occasional illustrations by Wagner.

In the publication chronology, Grendel Tales, in which other artists and writers played with the Grendel-verse, followed War Child, but the only one of these in the omnibus edition is Devil Child in volume 2. Following Grendel Tales, Devil Quest then led to Grendel Prime’s appearance in Gotham City in the 1996 miniseries. Past Prime, though, first appeared in print in 2000, but in story terms takes place right where the omnibus puts it. Years after Grendel Prime helps Jupiter Assante become the Khan, the cyborg has disappeared, and Jupiter has been assassinated. Devil Quest will show that a succession of increasingly unworthy Assantes succeeded him, but Past Prime follows a supporting character in War Child, Susan Veraghen.

In War Child, Susan was first Crystal Assante’s keeper (Crystal is Laurel’s daughter from a previous marriage, and a partisan for her half-brother.) Crystal seduces Susan, and they escape together, living in the forest until Jupiter returns to take the throne. Past Prime is narrated by Susan, picking up her life after Crystal has abandoned her, after she has been sidelined in Jupiter’s Grendels, and after the guilt she nonetheless feels for Jupiter’s murder (which is never fully explained) has driven her to become, essentially, a ronin. In reaction to her own aimlessness, Susan goes in search of Prime. Prime is called such because he is felt to be the height of what a Grendel can be. In the world of Past Prime, by contrast, the Grendels have become roving bandits of a sort: thugs and opportunists. For Susan, if not for Grendels generally, being a Grendel is about honor as well as strength. Finding Prime, then, is about her restoring her own sense of honor, and about finding herself again as a Grendel according to the original code established by Orion and embodied by Prime. To do this, she must reject not only what Grendels have become, but also the disaffected who have become revolutionaries intending to overthrow the Khanate and eliminate the corrupt Grendels. One of these revolutionaries is a woman that Susan falls in love with in the course of her journey; even though she recognizes the validity of her lover’s arguments, Susan remains steadfast in her intent to reclaim her mission as a proper Grendel. Here, finally and most explicitly, the creators explore the moral grey areas around the Khanate, and the idea of Grendel as a metaphor for global power. Susan fights with herself as much as with the world around her. That she remains loyal to her own sense of Grendel-ness is both an expression of her own strength, and, unsettlingly, a subjugation of self (in that she is fully aware of what the Grendels have become), and a rejection of that part of herself that is driven to fight injustice. We never learn what becomes of Prime and Susan after this adventure: is there some larger goal they will pursue? Will they try to reform the Grendels or the Khanate? Is there, in other words, any real attempt at social justice that the reader would find laudable, as a counter to the revolutionaries they defeat? The ambiguity is certainly complicated by what is revealed as the revolutionaries’ own violence and power-hunger; it’s not as if they are indicated to be as heroic as Susan’s lover thought them. Too, though, one might argue that their violence is itself an outgrowth of the Grendels’- that this is the dystopian world that “Grendel” has wrought. Ending on a Susan marching forward with Prime, we are with total moral uncertainty. Few novels of comparably epic narrative scope end on such a complex note.

Finally, it must be said that Past Prime underlines the extent to which Grendel is not only a testament to Wagner’s thematic ambitions and artistic accomplishment in crafting such an intricate epic, but to the virtues of writer/artist collaborative possibilities. In the omnibi, only two stories are written by anyone other than Wagner, Schutz on Devil Child and Rucka on Past Prime. But working with a huge range of artists in a huge range of styles, which in turn encouraged Wagner to take a huge range of approaches to storytelling, is an important part of why Grendel is a comics tour-de-force. As I’ve argued, the omnibus format allows Wagner to clarify the interrelationship of the parts to the whole in such a way as to reveal most fully and persuasively the nature of Grendel as a long-form narrative, to explore power and violence in all kinds of manifestations on all kinds of scales. Reading the title in collected, omnibus form, too, helps to reveal Grendel as an ambitious exploration of the aesthetic possibilities of graphic storytelling. I have no idea what kind of new territory Wagner can find at this point, let alone for Hunter Rose (vs. Lamont Cranston, I guess? I might be a bit behind on what’s going on with The Shadow these days), but I can’t wait to read it.